It is no small secret that I enjoy westerns. It is may even be my favorite genre, though I love many others. As such, I’ve done a lot of thinking about what makes a good western, and as a writer I’ve gone on that old fool’s errand of trying to boil a story down to its most basic structural elements.

A portion of my curiosity can be ascribed to the fact that “they just don’t make westerns like they used to,” and there’s a lot of reasons given that ultimately strike me as nonsense. Reasons like audiences got tired of it—which is a pretty blatant lie given the “The Great Rural Purge” of 1971, when CBS killed off most of its western and rural focused programming. This is also the excuse given for the imminent death of the superhero genre. And talking heads believe they’ve stumbled on some great new point when they draw the comparison. But I believe, they ultimately miss the forest for the trees. Audiences are exhausted, they say, while paying very little attention to what made the genres important and popular in the first place. That audiences might not like the new “western myth” or the new “superhero myth” being proposed is given very little attention.

I believe the western, as cowboy myth, operates on two levels. It works as a feedback loop, between American history and contemporary American society. There’s an important caveat with that last statement. There is the way contemporary society is and the way the talking heads, the media, the NGO’s, the whoever you want to blame at any given moment would like you to believe it is. Faking consensus is the foundation of most modern society. The feedback loop remains mostly organic. If you change the fundamentals of a story and it dies, this should be viewed as society rejecting it. If you change the fundamentals and it succeeds, you have now evolved the myth, you have found some spiritual truth that deeply resonates with a majority of the populace or a fandom.

This is important for writer’s and artists alike because you can’t create great art or change culture by moving backwards. Time and culture moves in one direction, forward. There are branching paths, of course, but it never moves backwards. Change is constant.

Ultimately, I believe the so called "death of the western" has less to do with it going out of style than it having been evolved into a dead end, much like the rest of American culture over the last fifty years. The anti-western truly was an apt myth for its times. But death always comes before rebirth, and I think the western will return, but it won’t look like the Traditional western that started it all or the anti-western that ended it all. It will look more barbarous, more dangerous, and again be apt for our times.

The Western as Myth

Central to the western mythos is the concept of Manifest Destiny. Manifest Destiny being the belief that American settlers and by proxy the American Republic was destined to expand westward and tame the continent. While this helps us establish the central theme of the western myth, some may find it hard to contextualize manifest destiny in the contemporary for the sake of our feedback loop. For this task I submit another word: progress.

John Truby in his book The Anatomy of Genres keys in on this central theme of the western and describes it as society vs the individual.

"Here lies the fundamental contradiction of the western hero: in blazing a path to the wilderness, the cowboy makes it possible for others to follow him and build the nation. The common people creating their homes out of the dystopian land are like the Israelites wandering in the desert. The cowboy hero is Moses."

Another way to think of this idea: A strong violent horse barbarian, in order to protect the woman he loves (who is most likely the daughter of a farmer), must stop a gang of other strong and violent horse barbarians from preying on the weak farmers. With this frame, we can immediately see the western as the anthropologically ancient story that it is, with farmers being the harbinger of civilization. Again, the idea being described is progress, or in this case civilizational progress.

In the book Comanches: The History of a People, T.R. Fehrenbach makes the argument that the introduction of the horse actually stunted the Comanche's civilizational progress. Hunter-gatherers are almost always preoccupied with survival, so much so, that they have no time or reason to build villages, much less cities. Farming is a first step on the tech tree towards civilization. This is doubly true when condemned to a nomadic life on foot. Necessarily, the evolutionary pressure of starvation then pushes some bright young man to come up with the idea of growing food instead of chasing it all over hell and back. Farming provides a food surplus. The people can survive the lean winter months off what they've grown in summer. They also no longer need to constantly move to new hunting grounds. This means permanent structures make sense, which leads to villages and eventually cities, and thus—civilization.

In fact, the Native Americans, broadly speaking, had already made this leap with the Mississippi Mound Culture established around 1200 A.D., which led to one of the largest native cities ever founded on the continent. The remains of this ancient city is known as Cahokia and its remains are preserved near modern day St. Louis.

By around 1400 A.D. this civilization collapsed for reasons that can only be speculated on now—drought, war, or the civilizational decay that necessarily follows human sacrifice. In some ways, the natives found at the time of European contact could be thought of as post-apocalyptic survivors, but aren't we all if you go back far enough (I long for Atlantis to return). Three apocalypses take place in the first eleven chapters of the Bible. Humanity’s story is one of collapse and rebuilding. Losing and conquering. From darkest night to brightest day, and back around again.

Regardless, the (re)introduction of the horse in the late 1600s meant that the Comanche no longer felt the evolutionary pressure to ever become farmers. The horse transformed them into ultra-violent super predators capable of treating the Buffalo herds as their own grocery store, and their neighbors 800 miles away as luxury boutiques for such things as more horses and women. They were also one of the only tribes that fought mounted and selectively bred their horses. They were so fierce that the Spanish, who conquered the Aztecs, decided it may be best just to leave them alone. Had the Comanche not met the Anglo-Saxon and German settlers flooding west in the 1800s, it does not seem farfetched to say that the next Genghis Khan could've been Comanche.

Digressions aside, by using the word barbarian we can see the Western's ancient roots. Structurally, it is quite an old story. It is the story of civilizational progress and the strong individual’s role in bringing it about. This is one of the reasons The Magnificent Seven could so smoothly adapt Kurosawa's Seven Samurai, almost beat for beat, and still be considered a quintessential western. Indeed, East does meet West.

Interestingly, Story Grid actually classifies the Western as Western/Eastern Genre. And from them, we find the central question that the western seeks to answer: "Is the autonomous, self-reliant individual in society dangerous to law and order or necessary to protect the powerless from tyranny?"

Put another way, and combining these two ideas—how does the individual relate to society and how does that affect civilizational progress?

Narrative Structure’s Role in Myth

As mentioned previously, I believe the western, as cowboy myth, operates on two levels. The first as a way of understanding American history, and the second, as a way of understanding and navigating contemporary American society. For a genre to be a best-seller it has to first and foremost operate on the latter level, by recontextualizing the contemporary in terms of the past. What I am not talking about is deconstruction or rewriting history, although this sort of structural analysis can and has been used for those ends. Deconstruction of myths is the real reason “the western is dead,” and supes are on life support. But once a myth dies, the answer is not to reanimate its corpse in the form of pastiche and parade it around like a weekend at Bernie’s. No, it has to be fundamentally remade, reconstructed in a way that satisfies the feedback loop that exists between our times and the past.

Progress is neither good nor bad. It is both simultaneously. That is the tension at play in the western. How the individual relates to society, and progress, is the central question the western strives to answer. What makes an emotionally satisfying answer to this question, thus fulfilling the purpose of myth and fantasy, looks very different depending on the current relative strengths of the individual in relation to current society (or its proxy in the form of government).

While I have been circling this idea for a while, it wasn't until Will Wright's book Six Guns & Society: A Structural Study of the Western published in 1975 that I read my own roughly-hewn thoughts repeated back to me. Wright takes issue with the anthropologists and scientists who say myth does not exist for modern man, as modern man has literature, science, and history to explore the world around him and no longer needs myth.

I tend to agree with this take, and would even go so far as to say Conspiracy Theories are valuable, broadly, as a form of modern myth, explaining spiritual truths and providing story context to a nonsensical (via information capture and institutional gaslighting) and increasingly hostile world. But again, likely for a different essay. The primary value of story and myth is to teach people how to navigate situations. The idea that modern man has no myths is absurd when they exist all around us.

Wright outlines four variations of the western myth which he then ties to the "attitudes implicit in the structure of American institutions" occurring at the time of their evolution. Wright takes a very economic facing approach, one that I feel takes too narrow a view on modern man and his relationship with society, yet I find his structural analysis very useful. Wright also identifies Four Axis on which the Western myth turns:

Inside Society/Outside Society

Good/Bad

Strong/weak

Wilderness/Civilization

Also important to Wright's framework is the idea of Narrative Sequence, which can most quickly be identified by the Inside Society/Outside Society axis and to some extent the wilderness/civilization axis. Good/Bad and Strong/Weak are important, but primarily act as weighted values on the social participants and the outcome.

The Classic Western Structure (1930 - 1955)

Wright correlates the narrative structure and the time period of the Classic Western structure with that of a market economy. The individual starts off clearly distinct, and separate from society, often even lower than the social group he is trying to enter: think the ex-gunman, drifter, outlaw, saddle tramp.

"Thus, in the classical western we have an aristocratic tendency with a democratic bias. Under threatening circumstances it is reasonable and proper to rely on a strong, elite group of men; but when the danger has passed, they must become equal with everyone else, a requirement, in fact, they have been fighting to ensure."

"Above all, it is an egalitarian society where no one, except a villain, sets himself apart from others. All are legally and morally equal, and though abilities differ everyone is assumed to be decent and kind. This is the society the hero chooses to join by surrendering his unique position of status and power; and this renunciation is necessary—if the hero did not give up his status, society would be different. If he maintained his position, the hero would change its egalitarian nature and create a powerful and undemocratic elite."

Below is the Classic Western Plot:

The hero enters a social group

The hero is unknown to the society

The society recognizes a difference between themselves and the hero; the hero is given special status

The hero is revealed to have an exceptional ability

The society does not completely accept the hero

There is a conflict of interests between the villains and the society

The villains are stronger than the society; the society is weak

There is a strong friendship or respect between the hero and a villain

The villains threaten society

The hero avoids conflict involvement in the conflict

The villains endanger a friend of the hero

The hero fights the villains

The hero defeats the villains

The society is safe

The society accepts the hero

The hero gives up or loses his special status

"This is the bourgeois ideal of a society based on interaction and communication as well as the concepts and actions of market individualism... "Equality"—the natural claim to status and power followed by the voluntary relinquishing of it—constitutes a remarkable narrative tribute to the strength of this bourgeois view of the "good society."

In short, the Classic western and its variations structurally support the fundamentals of a democratic republic and market economy. You can see the myth of George Washington embedded in the ending. The hero relinquishes his special status at the end, much the same way Washington supposedly decided that two terms was quite enough for any one man. America was to be ruled by an elected leader, not a king, and when the time came he voluntarily stepped down and reintegrated with the rest of the citizenry.

In the Classic Western, the man of action puts down his gun, steps down from his position as leader and hands the reins of governance back to the inept and weak town once it is saved from the villains. His happily ever after is quite often the transition from horse barbarian to longhouse, as there is quite often a love interest involved to facilitate this transition. In its most base form it is the aspirational tragedy of self domestication. The wilderness dies to make way for civilization and society.

The Vengeance Variation (1955 -1960)

The hero is or was a member of society

The villains do harm to the hero and to the society

The society is unable to punish the villains

The hero seeks vengeance

The hero goes outside of society

The hero is revealed to have a special ability

The society recognizes a difference between themselves and the hero; the hero is given a special status

A representative of society asks the hero to give up his revenge

The hero gives up his revenge

The hero fights the villains

The hero defeats the villains

The hero gives up his special status

The hero enters society

Here we have a variation of the Classic western, except society and progress are a bit further along. The hero starts as a member of society. Domestication has already taken place. He suffers some wrong at the hands of a villain, and society or the law is too weak or is already too corrupt to enact justice. So the hero rewilds, separates himself from society, and seeks punitive action against the villain.

Ultimately, the hero often gives up his revenge by the end, thereby upholding the values of a liberal democracy. That he is still forced to fight and kill the villains, is necessary for an emotionally satisfying ending, and another reinforcement of the classic western theme—fighting and killing is ok in the name of protecting the weak. Now he is doing it for the “right” reasons and not personal satisfaction.

The pillars and morals of the classic western remain intact. The feedback loop between the western and contemporary society where the rule of law is valued and respected is ultimately upheld even though it was originally questioned.

Most notably the Italian spaghetti westerns rejected this American variation in favor of a much more aristocratic ending. The hero takes his revenge and gains his own personal satisfaction, refuses to reintegrate into the weak and corrupt society, and rides off into the sunset, usually with a whole pile of gold bars or the price of a bounty. That this caused pearl clutching about amorality and violence in America is no surprise. The Roman Empire remains in all our hearts and minds.

Transition Theme (1950-1955)

Wright picks out a mere three films here as logical transition films from the Classic Western plot to that of the Professional Plot. The transition theme is a reversal of the Classic Western Structure. Where the Classic western maps a heroes path from estrangement to acceptance by society, the transition film maps the heroes journey from acceptance to estrangement with society. Wright submits High Noon, Broken Arrow, and Johnny Guitar as these three transitional films. In these movies society starts off strong, so strong in fact, that it is more powerful than either the heroes or the antagonists, and society itself is revealed to be the "big bad." Here the villains merely serve as plot device while society takes on the role of villain.

Broken Arrow and High Noon are both classic westerns, even if they ultimately come to the conclusion that the individual retains the moral high ground and decides against society. The pre-cursors for the anti-western exist here, in that society is irredeemably corrupt and weak and will eventually overwhelm the individual, but by keeping the hero a moralist, it manages to still uphold the classic western values. Remove the moral hero, and you would have an anti-western.

Professional Plot (1958 - 1970)

The heroes are professionals

The heroes undertake a job in return for money

The villains are very strong

The society is ineffective, incapable of defending itself

The job involves the heroes in a fight

The heroes all have special abilities and a special status

The heroes form a group for the job

The heroes as a group share respect, affection, and loyalty

The heroes as a group are independent of society

The heroes fight the villains

The heroes defeat the villains

The heroes stay (or die) together

It is the Professional Plot where we really start to get into anti-western territory. The Wild Bunch or Butch-Cassidy and the Sundance Kid are both westerns that use the professional plot, but ultimately decide on an anti-western theme. Typically, an anti-western requires that the heroes die at the end (my rules). And usually it is a meaningless death. The Magnificent Seven is a classic western with a professional plot, where a majority of the heroes die at the end, yet it is not an anti-western. This is because of the moral arguments being made. They die to save the society or Mexican farmers. The kid even gives up his dreams of being a gunfighter in order to become a farmer and marry the señorita he has fallen in love with, thereby fulfilling the demands of the Classic Western. Yul Brynner and Steve McQueen while they don’t integrate into society, move on like the wandering ronin they are, voluntarily stepping down from their position of power in the village.

Structuralism

More from Wright:

"In most analysis (anthropological), the primary interest has been in the social symbolism of the myth rather than in the movement of the story, the conflicts and resolutions of the plot. The narrative aspect of the myth has been taken for granted as a necessary framework for the expression of the symbolism, not particularly interesting in itself; like the stadium for a football game, it is useful for the game but does not need to be included in the commentary. By stressing the narrative structure of the western, I have tried to show that it is through the narrative action that the conceptual symbolism of the Western, or any myth, is understood and applied by its hearers (or viewers).”

“When the story is a myth and the characters represent social types or principles in a structure of oppositions, then the narrative structure offers a model of social action by presenting identifiable social types and showing how they interact. The receivers of the myth learn how to act by recognizing their own situation in it and observing how it is resolved.”

“Thus, it is in the narrative structure that the relationship between a myth and its society is most apparent, and it is because they have generally ignored the narrative dimension that most commentators on myths have interpreted them as revealing universal archetypes, biological traumas, or mental structures [he's taking shots at Jung and Freud here] rather than as conceptual models of social action for everyday life."

Now, Wright never mentions Joseph Campbell, who of course wrote The Hero with a Thousand Faces and condemned us to a billion permutations of the Hero’s Journey ( yes, I like a good hero as much as the rest of them), but they both appear to be speaking the same language. Campbell was much less concerned with archetypes than say someone like Jung, and much more concerned about the narrative structure and sequence of events that made up the heroic journey. In a way, Wright is attempting to accomplish the same thing here with regards to the Western myth.

"But for this very reason, history is not enough: it can explain the present in terms of the past, but it cannot provide an indication of how to act in the present based on the past, since by definition the past is categorically different from the present. Myths however, can use the setting of the past to create and resolve conflicts of the present. Myths use the past to tell us how to act in the present. In tribal societies, since the mythical past is the only past worth knowing, myths can stand for history. In our society they cannot, but they can fulfill a major function, which is to present a model of social action based upon a mythical interpretation of the past."

Keep in mind this book was written in 1975, far before “woke” culture was explicit, but definitely came after the cultural revolution of the 60’s. To those sick of the culture wars, every time Wright mentions "social action," I am sure it grates on the ears. I was unable to pick up on his personal political leanings, even if he does throw around the term bourgeois. So ultimately, I’m not sure if I have stumbled onto a Marxists university dissertation reprinted as a book on Western cinema. Probably, its a coin toss. Personally, I don't think he was approaching this analysis from a Marxist framework, but rather a purely structuralist one as it relates to myth and contemporary economic society. And overall, while I disagree with some of his correlations and analysis, I think the framework he provides is quite useful.

Simultaneously, this is quite obviously a structuralist analysis of the Western. Structuralists hold that reality can only be understood by the wider systems that shape individuals and events. Structuralo-Marxism is a school of thought that attempts to fuse the ideas of Marxism and structuralism. Now that is not to say that Structuralism is inherently Marxist, but Marxism tends to be inherently structuralist.

When we start talking structuralism, especially in the context of story and myth and subversion and social action, that should clue you in to how story and myth are subverted and colonized by the politically organized.

It's also possible to take issue with Wright's presentation of history as objective fact. If that was true, there would be no reason for certain political forces to actively attempt to rewrite it. By rewriting history, they are attempting to subvert the myth or even erase it all together. So called "message fiction," from the left or right so often fails because it wears its message on its sleeve. While I am no advocate for message fiction, I'm neither so naïve as to assume that all art isn't in some sense inherently political, either purposefully or subconsciously.

To truly plant seeds for “social action” in the minds of a reader or viewer, the message must be buried deep in the narrative structure—at the level of myth making. That is how you build culture or subvert it. That is how you edify or weaken. That is how you create mind viruses. Just because the blockbuster propaganda of today is sloppy does not mean it always was. Structuralism has become very important to Leftism, because it allows them to deftly deconstruct "enemy myths" the same way a crack team of ethnically ambiguous demolition experts might target the key beams in a skyscraper. But if we view structuralism as a tool for analysis, then we also start to see how it can be used to reinvent myths that jive with the time.

The problem with deconstruction is that it just kills a myth or story off. It doesn’t replace the story with a new one with lasting power. This is why we can have fifty years and one million iterations of the Classic western plot, but only ten years and a handful of anti-westerns before most everyone moves on from the genre altogether. For a story to have the sort of timelessness that gives it lasting power, it has to tap into some sort of inherent and optimistic truth.

For those looking to rebuild culture, it begs the question, can structuralism be used to rebuild or tweak new systems or new stories? Has this myth already organically started to emerge? Are outside forces trying to strangle it in its crib?

Anti-westerns

The Western is a good genre if reasonably done. It’s a morality play, and it went along that way for 100 years. I contributed to its downfall when I made The Wild Bunch. But notice, since we made it, almost all Westerns have gone to ultra-violent.

L.Q. Jones on his role in the Wild Bunch

Defining an anti-western is a messy science. Things get especially squishy when you start coming at it from a structural point of view. Things also get squishy when a protagonist displays homeric virtues but not liberal ethics.

In my opinion, it requires two main things from a structural point of view:

Amoral or villainous protagonists.

Society as the enemy

The protagonists die in the end

In my opinion, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and the Wild Bunch (1969) would probably be the templates for a structural anti-western. Ironic and telling, that both of these closed out the end of the culture revolution in America.

All kinds of westerns get classified as anti-westerns that I don’t believe belong there. There is an argument that any western that rejects the basic tenants of a liberal democracy is an anti-western, which is how you get lists filled with spaghetti westerns, or The Outlaw Josie Wales, Pale Rider, Unforgiven, and modern neo-westerns like No Country for Old Men, Hell or High Water, and Sicario.

The Outlaw Josie Wales is one of my favorites, and structurally it is 100% a red blooded Classic Western right down to the hero reintegrating into society.

No Country for Old Men definitely qualifies as an anti-western. The chaotic nihilism of Anton Chigurh playing stand in for modern society. The death of Llewelyn Moss. And the ineffective and terminally confused Sheriff Bell succumbing to time and progress itself.

My ultimate point is that we have to draw lines and try to carve out the placement and story beats and themes that turn a western into an anti-western if we are to start playing around with the myth and shaping it into something new. Or even defining that something new when it emerges.

Unforgiven, Hell or High Water, and Sicario are that something new in my opinion. Perhaps, even a bit ahead of their time in the case of Unforgiven. I think they represent an evolution of the western myth in a new direction.

The Returning West

Unforgiven (1992) would like you to believe it’s an anti-western for most of the whole movie. It spends almost its full run time picking apart the myth and the tropes that make a classic western. Society and its laws are corrupt. The hero was a murderous outlaw. Killing is meaningless and not cathartic. The west was nothing more than a legend. In short, everything about the myth is rotten to its core. America was built on a lie. If this was truly an anti-western, William Munny played by Clint Eastwood should die at the end in a blaze of glory and the Sheriff and the town should go on being corrupt.

But that doesn’t happen. The whole movie does a heel turn in the last 10 minutes. William Munny marches into the Saloon and lays down the law at the end of a gun in some of the most cathartic violence you’ve ever experienced. The whole argument the movie has spent the last two hours making is flipped on its head.

“That's right. I've killed women and children. I've killed just about everything that walks or crawled at one time or another. And I'm here to kill you, Little Bill, for what you did to Ned.”

It should be noted also that although William Munny was a murderous outlaw, he reformed after marrying his wife (now dead), and tried to become a better man. Whether this change actually stuck or not, or is possible, remains the central question of the movie throughout.

After Munny kills the corrupt Sheriff, played by Gene Hackman, and his acolytes, he begins to ride out of town but before doing so shouts that if they ever get out of hand again, he will ride back and burn the whole thing to the ground. The final scenes are Munny returning to his farm. Again, outside of society.

It should also be noted that what finally breaks this dam of violence loose on the corrupt town isn’t the whores that were cut up, or even the pursuit of the bounty, its a homeric loyalty to his friend Ned who’s body decorates the Saloon. It is Justice’s primordial father vengeance. The hero does not integrate into society in the end, or even give up his place as aristocratic avenger. His promise to come back and burn the town down demonstrates as much. No, he stands outside society as an avenging angel. The strong and violent individual who acts a balancing force against society and its petty tyrannies.

Hell or Highwater makes a similar argument for the supremacy of the individual and even the family unit. The whole movie is set against the backdrop of the 2008 recession and the corrupt banking institutions that have absorbed and subjugated the common man. The protagonists are bank robbers, with limited qualms about who they shoot back at. The Texas Rangers are the “good guys” who carry water for a fundamentally corrupt society built on the back of usury. The movie is half-western and half-crime thriller. It ends with the hero getting away. He uses the bank money to buy back the land that has a lien on it, just in time to lease the mineral rights and position his progeny on piles of generational wealth. He does not die (although his brother does), and the law does not win. In short, the movie asserts that providing for one’s family is a higher moral ideal than protecting usurers.

Where an anti-western demands the individual hero lose against the march of progress and an increasingly corrupt society, this new western shows how the individual can win. He wins by returning to more base and barbarous moral systems and leverages violence and wit against the society in order to recapture or protect his sovereignty.

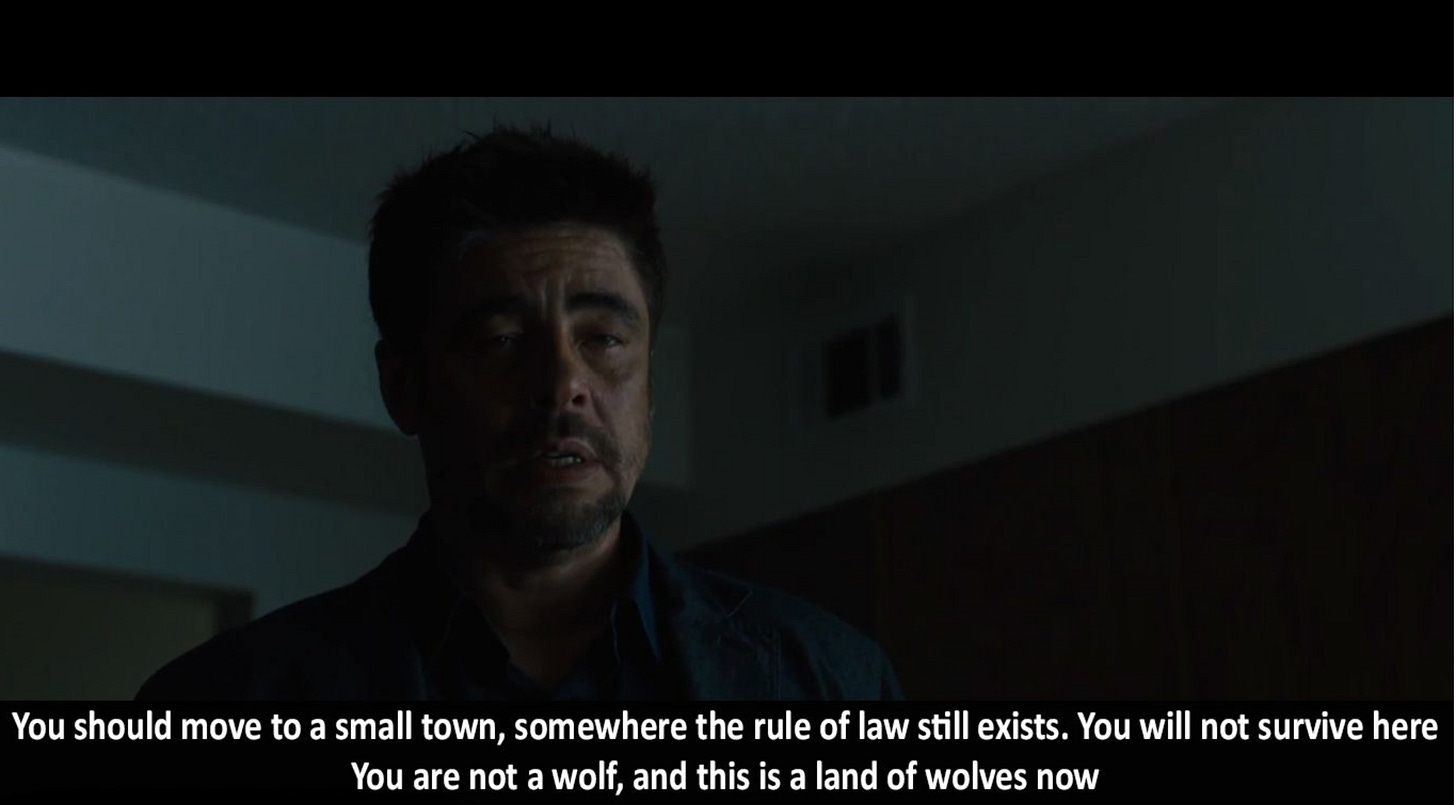

Sicario is much the same. Kate Macer, played by Emily Blunt, is the face of law and order. She is an FBI agent, a girl boss. She is the face of modern society and its institutions. But the frontier is pushing up from the border. As society grows more weak and inept, the edges begin to rewild. What is needed to quell its advance is pragmatic and targeted violence. Again, revenge fills in for justice in the form of Benicio Del Toro’s character Alejandro. The Cartel has murdered his family. He is now prosecutor turned hit man for the CIA. That he was a lawyer demonstrates quite viscerally how the law has failed to do its job in the face of this rewilding. And when justice is finally doled out, Alejandro kills the Cartel leader’s whole family. This is a return to the primitive. An eye for an eye is taken. A lineage is wiped out and the earth is salted.

I don’t believe anyone has tried to classify these westerns or these stories, maybe the argument that they are significantly different from what has come before has not yet been made. That they have been immensely successful and popular, demonstrates a positive feedback loop between contemporary society and the myth that holds a new valuable truth.

If we were to try to boil down this type of westerns basic parts, it would almost be the anti-western but reversed. Perhaps, we could call it the reactionary western or the Rewilding Plot. But I think the recipe would turn on the following structural elements:

Society and the law have lost legitimacy in the eyes of the individual

A strong individual must return to more primitive moral systems to win; perhaps even homeric virtues (physical prowess, courage, loyalty, guile and the fierce protection of one's family, friends, property, and, above all, one's personal honor and reputation).

The ending reinforces the value and sovereignty of the individual over the needs of the society. In short, society may remain corrupt at the end but the individual triumphs and leaves it a bit weaker or somehow changed while seperating himself.

I think the key to understanding this new sort of myth is to understand how it relates to contemporary society. Ask yourself, how does the average American relate to society and governance at large. A Republic for the people and by the people, hardly seems like a good faith understanding of what America looks like to most people post 2001 or 2008. Corporations, banks, and global NGO’s now seem to be bigger power players in the American government than any one group of little old citizens. But instead of an all powerful monstrosity, the empire appears to be crumbling at the edges. Every day, new gaps in law and order appear. Important institutions appear to be crumbling under a competency crisis. The average citizen is crushed by debt. Everywhere, people consciously or subconsciously recognize that things are slowly getting worse.

The frontier is reemerging, and it needs new heroes and new thought processes. New paradigms for navigating treacherous waters. Whether we know it or not, we feel like the Mississippi mound builders watching as our civilization of dirt slowly passes away, and on the horizon a new breed of warrior (re)emerges, from a time before our corn and human sacrifices—the horse barbarian. Men of old. This is the anxiety of our time, the feeling of it, and this is what the new western myth demands us to reflect.

You touched on two of my three favorite westerns: Hell or High Water ( the restaurant scene is 5 thumbs up), True Grit (also Jeff Bridges), and No Country for Old Men. I love the dialogue in all three, but especially True Grit. And No Country is close enough to Cormac McCarthy’s book that it’s great.

I really liked « Dead don’t hurt, » a western that used subtitles.